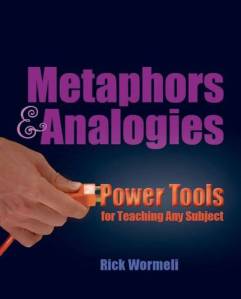

Stenhouse has put out a new book that I can’t recommend enthusiastically enough. Rick Wormeli’s Metaphors & Analogies: Power Tools for Teaching Any Subject

Stenhouse has put out a new book that I can’t recommend enthusiastically enough. Rick Wormeli’s Metaphors & Analogies: Power Tools for Teaching Any Subject adds to the canon of distinguished titles which deal with the topic of metaphor. His work, however, is so far the most practical title I’ve seen on the topic, offering teachers simple steps for improving their instruction through the use of metaphors and analogies. Every page provides subject-specific examples, allowing readers to easily understand the real-life applications to the classroom.

adds to the canon of distinguished titles which deal with the topic of metaphor. His work, however, is so far the most practical title I’ve seen on the topic, offering teachers simple steps for improving their instruction through the use of metaphors and analogies. Every page provides subject-specific examples, allowing readers to easily understand the real-life applications to the classroom.

My own forays into this topic began with George Lakoff’s now-classic Metaphors We Live By , which plainly illustrated the pervasiveness of metaphor in everyday language. While critics argued that the book was not well supported with research, just a brief look into its pages will convince

, which plainly illustrated the pervasiveness of metaphor in everyday language. While critics argued that the book was not well supported with research, just a brief look into its pages will convince  any reader that what Lakoff was attempting to prove through discourse alone was pretty self-evident (once exposed) and pretty remarkable as well. People do speak unconsciously in metaphors, all the time, and the metaphors they choose can tell us a lot about their preconceptions, perspectives, and prejudices on a topic. My personal copy of Metaphors We Live By

any reader that what Lakoff was attempting to prove through discourse alone was pretty self-evident (once exposed) and pretty remarkable as well. People do speak unconsciously in metaphors, all the time, and the metaphors they choose can tell us a lot about their preconceptions, perspectives, and prejudices on a topic. My personal copy of Metaphors We Live By contains hardly a page not scribbled with a comment or question; it did profoundly influence the way in which I approached reading and language arts instruction.

contains hardly a page not scribbled with a comment or question; it did profoundly influence the way in which I approached reading and language arts instruction.

Next came Marcel Danesi’s Poetic Logic: The Role of Metaphor in Thought, Language, and Culture , which was arguably more research based than

, which was arguably more research based than  Metaphors We Live By. Discovering the scientific and linguistic basis for everything Lakoff argued reinforced for me that metaphorical language is neither coincidental nor arbitrary. In Danesi’s own words:

Metaphors We Live By. Discovering the scientific and linguistic basis for everything Lakoff argued reinforced for me that metaphorical language is neither coincidental nor arbitrary. In Danesi’s own words:

The main goal of this book has been to take the reader on an excursion through an amalgam of facts, ideas, and illustrations that reveal how poetic logic works in making the world visible and thus understandable in human terms. Metaphor is a trace to poetic thinking, which constantly creates connections among things. This is why metaphors and metaforms have such emotional power—they tie people together, allowing them to express a common sense of purpose in an interconnected fashion.

What Rick Wormeli now brilliantly accomplishes through Metaphors & Analogies: Power Tools for Teaching Any Subject might be seen as a currency exchange. He takes the “hundred dollar ideas” of Lakoff and Danesi and turns them into “spending money” for the classroom. Wormeli shows how students can use metaphors to make connections between the concrete and the abstract, prior knowledge and new concepts, and language and image (neither Lakoff nor Danesi discussed visual metaphors at any length). Wormeli also goes beyond the passive museum experience of “let’s notice and appreciate the beauty of metaphors” to a workshop mentality of “let’s throw some clay on the wheel and see what we can form on our own.” Ultimately, his work is an impressive how-to on the subject.

might be seen as a currency exchange. He takes the “hundred dollar ideas” of Lakoff and Danesi and turns them into “spending money” for the classroom. Wormeli shows how students can use metaphors to make connections between the concrete and the abstract, prior knowledge and new concepts, and language and image (neither Lakoff nor Danesi discussed visual metaphors at any length). Wormeli also goes beyond the passive museum experience of “let’s notice and appreciate the beauty of metaphors” to a workshop mentality of “let’s throw some clay on the wheel and see what we can form on our own.” Ultimately, his work is an impressive how-to on the subject.

But what’s in it for teachers of literature? So many of Wormeli’s examples are based in math, social studies, and science that Reading and Language Arts teachers might wonder what’s in it for them.

Rather than construct an argument, let me instead offer a simple example.  Below is an excerpt from Wendelin Van Draanen’s Flipped

Below is an excerpt from Wendelin Van Draanen’s Flipped (grade level equivalent 5.5). How many single and extended metaphors can you spot? And more importantly, what additional (between the lines) information can they provide if the reader is alert enough to notice them?

(grade level equivalent 5.5). How many single and extended metaphors can you spot? And more importantly, what additional (between the lines) information can they provide if the reader is alert enough to notice them?

My sister, on the other hand, tried to sabotage me any chance she got. Lynetta’s like that. She’s four years older than me, and buddy, I’ve learned from watching her how not to run your life. She’s got ANTAGONIZE written all over her. Just look at her – not cross-eyed or with your tongue sticking out or anything – just look at her and you’ve started an argument.

I used to knock-down-drag-out with her, but it’s just not worth it. Girls don’t fight fair. They pull your hair and gouge you and pinch you; then they run off gasping to mommy when you try and defend yourself with a fist. Then you get locked into time-out, and for what? No, my friend, the secret is, don’t snap at the bait. Let it dangle. Swim around it. Laugh it off. After a while they’ll give up and try to lure someone else.

At least that’s the way it is with Lynetta. And the bonus of having her as a pain-in-the-rear sister was figuring out that this method works on everyone. Teachers, jerks at school, even Mom and Dad. Seriously. There’s no winning arguments with your parents, so why get all pumped up over them? It is way better to dive down and get out of the way than it is to get clobbered by some parental tidal wave.

The funny thing is, Lynetta’s still clueless when it comes to dealing with Mom and Dad. She goes straight into thrash mode and is too busy drowning in the argument to take a deep breath and dive for calmer water.

And she thinks I’m stupid.

The fact is, for students to read with comprehension and appreciation, they must be able to recognize and dissect both simple and complex analogies. And for students to be able to explain their own understandings of difficult concepts (no matter what the discipline), they must be able to describe those concepts through metaphors and analogies.

I highly recommend Metaphors & Analogies: Power Tools for Teaching Any Subject for teachers looking to advance their own practice as teaching professionals. As always, Stenhouse offers you a preview of the entire book at their site.

for teachers looking to advance their own practice as teaching professionals. As always, Stenhouse offers you a preview of the entire book at their site.

September 25−October 2, 2010 is Banned Books Week. No, my calendar isn’t broken, but I figure, what wait?

September 25−October 2, 2010 is Banned Books Week. No, my calendar isn’t broken, but I figure, what wait?. You’ll be surprised what’s there! It’s actually a pretty decent list of must-reads.

Stenhouse has put out a new book that I can’t recommend enthusiastically enough. Rick Wormeli’s

Stenhouse has put out a new book that I can’t recommend enthusiastically enough. Rick Wormeli’s  any reader that what Lakoff was attempting to prove through discourse alone was pretty self-evident (once exposed) and pretty remarkable as well. People do speak unconsciously in metaphors, all the time, and the metaphors they choose can tell us a lot about their preconceptions, perspectives, and prejudices on a topic. My personal copy of

any reader that what Lakoff was attempting to prove through discourse alone was pretty self-evident (once exposed) and pretty remarkable as well. People do speak unconsciously in metaphors, all the time, and the metaphors they choose can tell us a lot about their preconceptions, perspectives, and prejudices on a topic. My personal copy of  Metaphors We Live By. Discovering the scientific and linguistic basis for everything Lakoff argued reinforced for me that metaphorical language is neither coincidental nor arbitrary. In Danesi’s own words:

Metaphors We Live By. Discovering the scientific and linguistic basis for everything Lakoff argued reinforced for me that metaphorical language is neither coincidental nor arbitrary. In Danesi’s own words: Below is an excerpt from Wendelin Van Draanen’s

Below is an excerpt from Wendelin Van Draanen’s